Just about everything you need to know about a whisk(e)y is on the bottle.

Ah whisky, the brownest of the brown liquors. We love it in all its many forms (and spellings), from the softest Japanese whisky to the peatiest Scotch and everything in between. Whisky is a testament to human ingenuity (figuring out how to turn a grain from inedible grass into a life-affirming liquid? Bloody genius) and a spirit that has stamped its authority from straight sipper to cocktail main event. Oh yeah, whisky is grand.

To quickly recap, whisky (or whiskey, if it comes from Ireland or the US) is a spirit made from grains like barley, wheat or corn. First, the grain is fermented and then distilled, which concentrates all the flavours and alcohol content, and then (almost always) aged. That’s just the general process, though – it’s the different grains, regions, barrels, ageing lengths and a million other choices that give each whisky a different flavour.

Unless you’ve already tried it, the best way to figure out what a bottle of whisky could taste like is by reading the label. And if you don’t know what you’re looking at, reading a whisky label can feel like deciphering hieroglyphics. Honestly, every line sounds like a gag – ‘cask strength’, ‘Lowland malt’, ‘Oloroso sherry barrel-aged’, ‘non-chill filtered’. Does any of that actually mean anything, or is it just a big joke by Big Whisky?

As it turns out, it’s all pretty straight-forward once you get the gist. Here’s what we mean.

You can think of whisky a little like wine in that where it comes from can make a difference to how it tastes. Although, unlike wine, most of the time it doesn’t. Confused? Yeah, sorry about that.

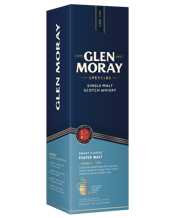

Here’s the lowdown: In wine, weather and location make a big difference. It’s called terroir and it basically refers to how a wine tastes like where it was grown and made. In whisky, terroir isn’t really a thing (it’s a lot harder to reflect those subtle characters when distilling something), but whiskies can still taste like a region in some ways. This is more of an intentional stylistic thing and you’ll mostly see it in Scotch whisky. For example, whiskies from Islay are often super smoky (or ‘peaty’), Lowland whiskies have historically been light and delicate, and Speyside malts are often fruity or nutty.

If you expand the idea of region to include a country as a whole, that might still tell you something helpful. For instance, whisky in Australian climates tends to age faster than in Scotland, while American whiskies often include corn, which can make the whisky soft and sweet. Region won’t tell you a lot specifically, but it can give you some hints.

If you’ve ever heard of moonshine or seen Irish poitín then you’re talking about a clear, unaged whisky – everything else has been aged to some degree (often by law). Whisky is aged (usually in barrels made from oak, just like wine) because it adds extra flavours and both the wood and time take the harsh edge off. The type of oak, whether that barrel previously held anything else (which we’ll cover in a min) and how long the whisky was aged for will all make a big difference to the final flavour. Generally speaking, the longer the whisky is aged, the stronger the flavour extracted from the barrel will be.

When you see a whisky on the shelf, it’s probably going to say how old it is with a number – something like 12, 15 or 18 years. Whether it’s a single malt, single grain or blended whisky, the number reflects the youngest whisky in the bottle. ‘Single batch’ whiskies are just from one distillation and all the same age, so the number on the bottle is exactly what you’re getting there.

So much of a whisky’s flavour is due to the barrel it’s aged in and, if you pay attention to the label, it means you should be able to get a good idea of what a whisky tastes like. Almost all barrels are made of oak and even that imparts flavour – American oak often gives vanilla or coconut notes, for instance, but you’ll quite often find whisky aged in barrels that previously held something else. And that, friends, is a big help when it comes to flavour.

Whisky often gets aged in ex-sherry barrels, which tends to lend a rich, fruity flavour, but ex-bourbon barrels are getting more common now, too, and these give off sweet butterscotch sorts of flavours. If you’re keen on a particular flavour profile in a whisky you try, make a note of the barrel type on the label.

Wherever it’s from, whisky is usually around 40 to 45% ABV. That’s just a standard sweet spot and, in some countries, 40% is actually the legal minimum. Stronger whiskies definitely exist, though, and you’ll often see these labelled as ‘cask strength’.

Usually, whisky comes out of the still at some ungodly strength – 60 to 70%, or even higher. Distillers often dilute that whisky a little to what’s called ‘filling strength’ and it loses a bit of its alcohol over time through evaporation (called ‘the angel’s share’) but, even still, it remains pretty darn potent. Usually, water is added to the whisky again before bottling to bring it down around 40% but, if the distiller doesn’t do that, you get a cask-strength spirit.

Cask-strength whiskies aren’t for the faint of heart, but they definitely have a few things going for them – flavour, for one. While the high alcohol content can absolutely overpower a whisky, sipping on something that hasn’t been diluted means you’re getting the full whack of flavour. It’s a unique, potent experience.

Most of what we’ve looked at has been really zoomed-in info about whisky – what kind of barrel it aged in, how old it is, its strength – but the overall style is a really good place to start, too. Here, ‘style’ means the broad categories within whisky, such as:

Bourbon: Often a sweeter, lighter style from the US

Scotch: Produced in Scotland and made from barley, you’ll often get a malty, biscuity flavour. Keep in mind all those regional variations, though.

Irish whiskey: Produced in Ireland and usually triple-distilled, so smoothness is a feature

Rye: A little spicy and grassy

Peated: Smoky

The point with style is this: if you had a spicy rye or a smoky peated whisky once and you’re looking to recapture the magic, this is something you can definitely find on the label. You might never find the exact same flavours, but at least you’ll know you’re in the ballpark.